In order to understand current economic scenario, let’s consider what happened during the Great Depression which started in 1929. Over the next four years, GDP per person (per capita income) went down by 20%. The impact of this fall in per-capita income on private consumption was huge. As Nobel Prize winning economist Robert J. Shiller writes in Narrative Economics: “Sales of new cars by Ford Motor Company… fell 86% from 1929 to 1932.” This fall in sales leads Shiller to ask: “Why was the feedback loop so severe?”

The answer lay in the mind of consumers. According to Shiller, “Those who already owned a car decided to keep the car going rather longer. Those who did not own a car, decided to continue taking public transportation.” For those who lost their jobs, it obviously made sense to postpone purchasing a car. Even those who were not impacted by the Great Depression postponed their car purchases (and purchases of other thing as well) given that they had a huge fear of losing their jobs.

This feedback loop hurt economic activity and destroyed more jobs in the process.

As Shiller writes: “Some people postponed buying a car or other major consumer items, which led to loss of jobs in the auto and consumer-products industries, which led to more postponement, which led to a second round of jobs loss.”

All this impacted consumer confidence and business confidence of that era. If the consumer confidence is high, the consumer will spend, the businesses will invest and the government will earn higher taxes, which it can spend on its programmes. Nobody understands this better than the politicians of the day.

If all this sounds familiar, that’s because parts of this playbook are relevant in India today. Of course, India is nowhere near a depression or even a recession. The economy is going through a slowdown in economic growth . But the feedback loop is in place—and Indian politicians and policymakers have also tried to talk up the economy.

Major Concerns in current Indian Economic Scenario.

Structural Issues

To be sure, banks have shied away from financing large corporate projects, but whether this was due to risk aversion or the lack of new investment demand is a moot question. The steep fall in manufacturing and construction, and stagnant private investment — which led to the fall in GDP. Given the complex problems that plague many sectors, separating demand and supply factors will be a difficult exercise.

For instance, the power sector is in an existential crisis (non-honouring of PPAs, non-payment of dues, falling tariffs, etc) which has led to the scaling down or even closure of many power plants, a fact that could explain the fall in power generation in the IIP as well as declining manufacturing demand. Likewise, the stagnation in private investment, even after reduction in interest rates and tax rates, points to issues beyond demand — these could be due to excess capacities created in the past, a preference for short-term profit or a simple lack of will.

The belief that the slowdown is demand-driven, and therefore cyclical, seems based on hope. The play of structural factors cannot be ignored. First, the fact that private household consumption drives the economy (over 50 per cent of the GDP), can be misleading. The fact is, we are still a low-middle income country with a per capita GDP of around $2,000, and nearly 80 per cent of our consumption expenditure consists of spending on essentials.

We do not know much about consumption inequality, but there is a high level of income inequality. According to the World Inequality Report 2018, the top 10 per cent of India’s population got 54 per cent of all income while the bottom 50 per cent shared only 15 per cent. A skew such as this can impact demand in sectors like automobiles or consumer goods.

Employment pattern

The other structural problem relates to employment. Our labour markets have many growth-impeding rigidities — a low labour force participation ratio (which means a large section of working-age population, mainly women, choose not to work); a high percentage (over 70 per cent) of rural labour ostensibly engaged in agriculture, but adding little to productivity or income; and a large informal work structure, where reportedly about 46 per cent people are self-employed and 20 per cent casually employed, making income estimation little more than guesswork for two-thirds of the labour force.

The sectoral Gross Value Added (GVA) data as well as income tax data reinforce these facts. A large GVA signifies a higher share of wage incomes and capital surpluses. Thus, while agriculture had high value addition (78 per cent), its share in the national income was small because of the large labour force working at low or zero wages. In contrast, the services sector contributes over 50 per cent of the GDP and also has high value addition, but employs a far lesser proportion of labour (about 25 per cent). The combination of low per capita GDP and high income skew has, not surprisingly, led to a low tax-GDP ratio.

The newly-minted economics Nobel laureates have eloquently described why it is difficult to explain economic growth, much less policies that will lead to equitable growth. But they also point to the existence of inefficiencies and misallocations that present actionable opportunities for governments.

Getting to a $5-trillion GDP may help us cross over to upper-middle income status, but unless the growth is equitable and broad-based, the economy will be continue to be susceptible to gyrations of the kind witnessed now.

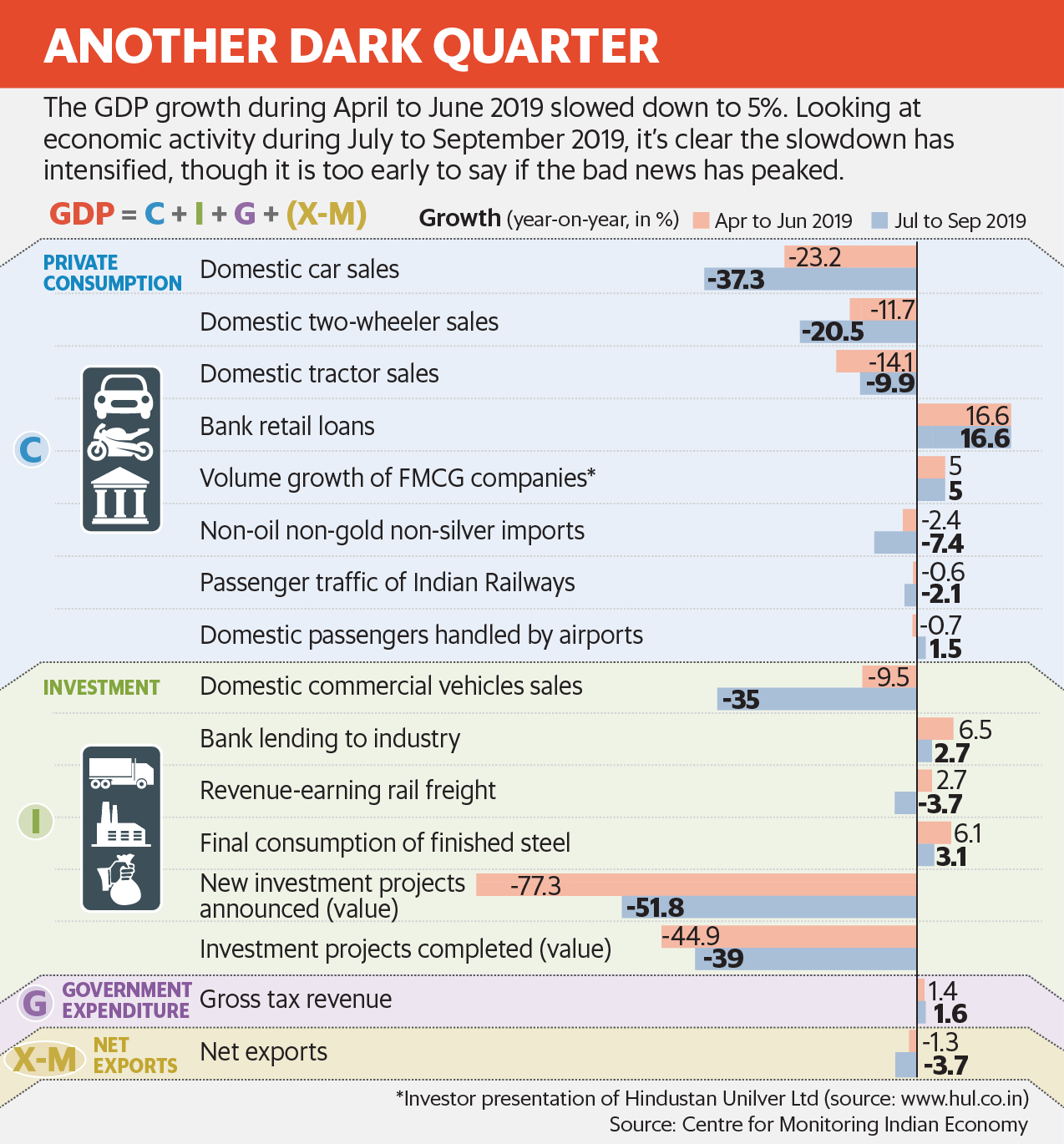

Clearly, the situation during July to September 2019 has only worsened in comparison to April to June 2019. The stock market might be doing well thanks to a few selected stocks rallying, but that hasn’t been able to lift the mood across the economy.

All in all, the psychology of the economic slowdown has well and truly set in.

To be continued…

Thank You!!

K. Trivedi & M. Sodagar